Francis Thackeray [1], Eddie Odes [2], David Lambkin [2]

1 Evolutionary Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa.

2 Independent Researcher.

Introduction

Eleven years before his death in 1616 William Shakespeare paid £440 pounds for a tithe deed which gave him the right to be buried inside Holy Trinity Church (Fig. 1) in Stratford-upon-Avon, in the chancel. This was an extraordinary privilege. It meant that he would be spared the awful possibility of his skull and skeleton being eventually tossed into a “charnel bone house” outside the church. In at least some cases, when the churchyard was full, skeletons from old graves would have been dug up and discarded in the charnel house. The latter has been destroyed since Shakespeare’s time

Apart from spending £440 pounds for the protection of his mortal remains within the church, Shakespeare is said to have written his own epitaph for a tombstone: “Cursed be he who moves my bones”. It has long been assumed that his skull and skeleton are still beneath that particular tombstone (or “ledger stone” to use correct terminology), but is this necessarily correct ?

Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) in HTC

In 2015 Professor Kevin Colls (Staffordshire University) and Erica Utsi (2017) conducted non-invasive Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) in HTC with permission from relevant church authorities. They concluded that there are in fact bodies within the graves, not in coffins but presumably enclosed in shrouds. The bodies had been buried at a depth of 3 feet.

Curiously, the skull in the grave attributed to Shakespeare was apparently missing. Perhaps not coincidentally there is a story based on two articles in the Argosy magazine, published in 1879 and 1884 under the name of “A Warwickshire Man”, stating that it had been stolen in about 1794 (Friends of Shakespeare’s Church, 2016; Argosy 1879, 1884). Allegedly the skull attributed to that of the Bard had been found at a depth of 3 feet. This would seem to correspond to GPR data for skeletons, giving credence to some extent to the story in the Argosy articles.

On the basis of GPR, Kevin Colls stated in a television documentary (Arrow Media, 2016) that “it’s very, very convincing to me” that Shakespeare’s skull “is not at Holy Trinity at all”. This has stimulated a search for it elsewhere.

The Beoley Skull

In a recess within a crypt at St Leonard’s Church (Fig. 1) in the village of Beoley (less than 30 km away from Holy Trinity Church), there is an isolated cranium (Appleyard, 2016) which (for purposes of reference) we call “The Beoley Skull” (Fig. 2). Allegedly it is the skull of Shakespeare, a claim based on the Argosy articles (Friends of Shakespeare’s Church, 2016). In 2015 and 2016 permission was given for it to become the subject of non-destructive investigation (without moving it), involving laser surface scanning and the use of a Faro Arm to produce a 3D three-dimensional model. Forensic facial reconstruction was undertaken by Professor Caroline Wilkinson of Liverpool John Moores University, indicating that the Beoley Skull represented an elderly woman, about 70 years old (Arrow Media, 2016). This means that the allegation that it represented Shakespeare should be dismissed.

In a Blog posted by Graham Appleyard (2016) and in an independent interview (Thackeray, 2025a) it was suggested that the Beoley Skull was that of Anne Hathaway, Shakespeare’s wife (Fig. 2), who died at the age of 67 years, corresponding closely to the age estimated by Caroline Wilkinson for the female skull. Anne Hathaway’s grave is adjacent that of her husband.

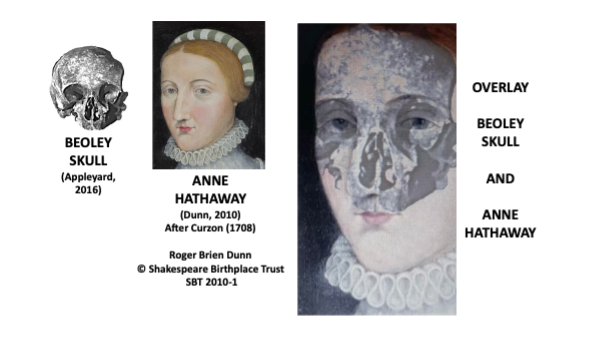

Photographs and overlay

Fig. 2 shows our overlay based on images of the Beoley Skull (Appleyard, 2016) and a portrait of Anne Hathaway (by Roger Brien Dunn, Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, SBT 2010-1, Asset 11287). The latter was painted in 2010 based on a sketch by Sir Nathaniel Curzon in 1708, itself allegedly based on a painting from the time of William Shakespeare (Scheil, 2018). The correspondence between skull and portrait appears to be remarkably good, but we do not claim that this constitutes proof that one individual is represented.

Questions

It is useful to raise issues in the context of the order of graves of the Shakespeare family in the chancel of Holy Trinity Church. The Bard, having died in 1616, was the first to perish among five relatives. As such, at least hypothetically, he could have been buried first in Grave Number 1 (Position #1) on the extreme left in a row adjacent the chancel wall, as suggested by Appleyard (2016) and independently by Thackeray (2025a). However, his gravestone is in Position Number 2. Anne Hathaway’s gravestone is Number 1 in the row despite being the second in the family to die.

The ledger stones would initially have loosely covered soil before being fixed in positions as they are today. The possibility that the stones became misplaced cannot be excluded (Appleyard, 2016), especially in view of renovations that may have occurred at one or more intervals within the past 400 years. Several questions arise:

If the answers to these questions are yes, the apparent correspondence shown in Fig. 3 might be explained, thus supporting a hypothesis that the Beoley skull is that of Anne Hathaway.

Thought Experiments

“Thought experiments” are not new to science. Albert Einstein conducted them to chase atoms (“in his mind’s eye” to quote from Shakespeare’s Hamlet), leading on to his theories of relativity. Such thought experiments typically concern activities which would be difficult or impossible to accomplish in practice.

In this exploratory study our thought experiment involves potential DNA analyses of teeth or bones of several individuals, if this were ever to be permitted by the Church of England (a highly unlikely possibility through Parish Councils up to the King), without disturbing bones of the body in Position # 2 (attributed to William Shakespeare, associated with a curse). The experiment is to be undertaken ideally on the following individuals, recognising that there are no extant male direct descendants of the Bard and Anne Hathaway.

1 The Beoley Skull (potentially Anne Hathaway).

2 Susanna Shakespeare Hall (daughter of William and Anne).

Susanna Shakespeare Hall is in Position #5 in the chancel, and was the last to die in the family sequence of five individuals. Question: Does mitochondrial DNA of Susanna and that of the Beoley skull (perhaps Anne Hathaway) tell us that this represents a mother-daughter relationship ?

3 The skull and skeleton under gravestone # 1 in Position # 1.

Questions: Does DNA tell us (potentially from a Y chromosome) that this individual (Person # 1) was a male (corresponding potentially to the Bard) ? Does age analysis tell us that this individual was about 52 years old (also corresponding potentially to the Bard) ? If a Y-chromosome is detected (indicating a male in the case of Person # 1), can the DNA of this individual (in Position # 1) be related genetically to that of any living male with the Shakespear(e) surname, directly descended from Richard Shakespeare (1510-1561), grandfather of the Bard ?

5 Any deceased male direct descendant of Richard Shakespeare ?

If we cannot identify any living male direct descendant of Richard Shakespeare, what about skulls and skeletons of deceased male direct descendants buried in England or elsewhere, including India where a number of Shakespeare(s) lived within the last 200 years ?

6 DNA analysis of Captain Francis Shakespear (1864-1905)

Allegedly (according to genealogical records of Wikitree), a deceased direct descendant of Richard Shakespeare (Wikitree Shakespeare-137, grandfather of the Bard) was Captain Francis Shakespear (Wikitree Shakespear-289). He was born in Ireland in 1864 (exactly 300 years after the birth of William Shakespeare), and died from a stroke in 1905 in northern India at a place called Prayagraj, in the region of Uttar Pradesh. We know exactly where he is buried in the Cantonment Cemetery in Prayagraj (Find-A-Grave Memorial ID 893 75159). The grave is very simple, with a low rectangular outline of cement and a cross. Theoretically (in terms of our thought experiment, through legal authorities) it would be possible to obtain small samples of bones and teeth for DNA analysis. Remarkably, his Y-chromosomal DNA can be expected to be that of William Shakespeare because they shared a common male grandparent, Richard Shakespeare. This way we would be able to identify the Bard’s Y-DNA without trying to examine any part of his own body, wherever it may be.

Conclusion

This note raises questions which are difficult to answer, but we direct attention in particular to the hypothesis that the Beoley Skull is that of Anne Hathaway, based on possibilities recognised independently by Appleyard (2016) and Thackeray (2025a). Our study is new in the sense that we have created an image (Fig. 2) which is an overlay based on part of the Roger Brien Dunn portrait of Anne Hathaway (Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, SBT 2010-1) and the Beoley Skull (Appleyard, 2016). We have considered a thought experiment, suggesting that William Shakespeare (a 52 year old male) is buried in Position #1 on the extreme left of the row of Shakespeare family members. The thought that a small sample of his femoral bone indicates the smoking of Cannabis can be considered (Thackeray, 2025b). Apart from this, we recognise that theoretically it would be possible to identify the Y-DNA of the Bard by examining the teeth and skeleton of a distant male relative, including Captain Francis Shakespear who (like the Bard) was descended from Richard Shakespeare, allegedly their common ancestor. If there is correspondence between the Y-DNA of Captain Francis Shakespear and that of Person # 1, we would be in a position (through our thought experiment) to infer that the body of the latter is that of William Shakespeare. Since there is no curse attached to the gravestone in Position # 1, his body could (in terms of our thought experiment) be the subject of detailed scientific study in the same way that the skull and skeleton of King Richard III were excavated and studied, including DNA analysis (Grey Friars Research Team et al (2015).

Appendix

According to the genealogical Wikitree source, Francis Thackeray (a co-author of this article) is apparently a first cousin of William Shakespeare nine times removed (Wikitree Shakespeare-1 and Thackeray-116). On the basis of secure evidence, he is a second cousin (twice removed) of Captain Francis Shakespear (Wikitree Shakespear-289) who lived in India. William Makepeace Shakespear corresponds to William Makepeace Thackeray. Similarly, John Talbot Shakespear corresponds to John Talbot Thackeray. The Shakespear(e) and Thackeray families are related by virtue of marriage between Mary Anne Shakespear (born 1793, direct descendant of Richard Shakespeare) and Francis Thackeray (born 1793, son of William Makepeace Thackeray senior).

Acknowledgements

The Shakespeare Birthplace Trust curates the Anne Hathaway portrait by Roger Brien Dunn (2010), based on a sketch by Sir Nathaniel Curzon (1708), allegedly from an Elizabethan original; SBT 2010-1, Roger Brien Dunn © Shakespeare Birthplace Trust https://images.shakespeare.org.uk/asset/11287/ Graham Appleyard (2016) posted an image of the Beoley Skull. Don MacRobert, Patricia Glyn, Conrad Penny, Desire Brits and Kevin Schürer are thanked for opportunities to discuss ideas related to graves in Holy Trinity Church in Stratford-upon-Avon.

References

Appleyard, Graham. 2016. Shakespeare’s skull or Anne Hathaway’s found? Whose skull is missing ? https://therealchart.blogspot.com/2016/04/shakespeares-skull-or-anne-hathaways.html

Argosy. 1879. How Shakespeare’s skull was stolen, circa 1794. Argosy magazine.

Argosy. 1884. How Shakespeare’s skull was lost and found. Argosy magazine.

Arrow Media 2016. Secret History: Shakespeare’s Tomb, broadcast on Channel 4, April 2016.

Friends of Shakespeare’s Church. 2016. How Shakespeare’s Skull was Stolen and Found, with contributions from Mairi Macdonald, Ronnie Mulryne, Patrick Pilton, Margaret Shewring, Patrick Taylor and Mike Warrillow. Friends of Shakespeare’s Church, Stratford-upon-Avon.

Grey Friars Research Team, Kennedy, M and Foxhall, L. 2015. The Bones of a King: Richard III Rediscovered. John Willey and Sons, Chichester.

Scheil, K.W. 2018. Imagining Shakespeare’s wife: The afterlife of Anne Hathaway. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Thackeray, J.F. 2025a. Storycatcher podcast hosted by Patricia Glyn. 31 October, 2025. https://storycatcher.co.za/podcasts/

Thackeray, F. 2025b. Use of cocaine and cannabis in 17th-century Italy and England, with reference to Shakespeare. South African Journal of Science, 121 (9/10): 1-3. https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2025/21465

Utsi, E.C. and Colls, K. 2017. The GPR investigation of the Shakespeare family graves. Archaeological Prospection 24 (5): 335-352.

This blog was inspired by my friend Patricia Glyn’s trip to the Waterberg in search of stories for her celebrated Storycatcher podcasts.

You feel it sometimes as a slight shiver down your spine when driving alone through the African bush. It might be the sight of a small wind pushing cloud-shadows through the grass, or a lonely thorn-tree standing dark on the skyline. These images pierce you like an arrow; and you know, without doubt, that you’ve seen it all before.

That sense of déjà vu can be scary; especially when you know you’ve never been near that particular place in your whole life. But the feeling of deep familiarity persists, and nudges you to acknowledge connections that go way back beyond the ticking seconds of your own brief life to memories that whisper from deep within the history of our species. Maybe even earlier.

It was the beautiful and mysterious Waterberg that taught me a huge personal lesson about that creepy déjà vu sensation. I’ll try to explain.

In the early 1980s, my friend Suzie Gregorowski and I often drove up from Jo’burg to Clive Walker’s Lapalala Wilderness in the Waterberg, staying at one or other of the original camps. They were all very rustic, all delightful, and had evocative names: Mukwa, Lepotedi, Mopane, Tamboti, Marula. Marula was our favourite. It dated back to the time when retired Kenyan hunter Eric Rundgren first bought a tract of wild country in South Africa and built himself a simple Kenyan-style camp at Lapalala. It was spartan and perfect, the sort of place Suzie and I knew well from our travels in east and central Africa.

There were no doors or windows, just bamboo blinds. There was a wood-fired donkey boiler, a genet that visited at dusk, a huge resident leguaan that often strode in bold reptilian fashion right into the kitchen, and rock pools a little way up-river where we could swim. Marula was the perfect escape from spurious deadlines and nasty ad agency politics. We could burn our fingers on cooking coals, get pricked by thorns and walk wherever we wanted to. We usually went barefoot, a kikoi knotted over one shoulder, a stick in hand. Evenings we spent sitting quietly at our camp fire with sundowners, listening for nightjars and owls.

And it was at Lapalala that I got a real spectral shiver of existential loneliness. The sky above was a celestial marvel – the Milky Way a spill of clotted cream, the sky aglitter with stars from horizon to horizon. And I felt a sudden eerie sense of insignificance – something like the one described so vividly by professor of biology Ursula Goodenough in her wonderful book ’The Sacred Depths of Nature’.

‘I was perhaps twenty, and I went on a camping trip where I found myself in a sleeping bag looking up into the crisp Colorado night. I was overwhelmed with terror. The panic became so acute that I had to roll over and bury my face in my pillow.’

Most of us don’t feel cosmic alienation as intensely as young Ursula. But the sheer vastness of the universe can inspire a chilly sense of irrelevance in even the most literal-minded. Think about it. Our tiny blue planet is adrift in a sea of eternal darkness. There are between 100 billion and 2 trillion galaxies in the observable universe, a total of maybe 200 billion trillion stars, any number of which might possess Earthlike planets. No wonder we feel unimportant.

But we shouldn’t. We are linked intimately to the past and to each other. It was ancient evidence of this deep kinship that compelled me to accept that strong bonds tethered us to the whole universe: the Waterberg’s dinosaur fossils and footprints, the nearby presence of not-yet-human ancestors, ancient dry-stone forts, San Bushman cave art, an Afrikaans poet’s researches into the soul of baboons, and a discovery made in 1957 by a gifted woman physicist. These disparate things convinced me of the link.

The first evidence was startling.

I no longer remember the name of the camp where we stayed. It was situated quite close to the river, and a huge krantz reared up on the far bank. San Bushmen first came to this area about 2000 years ago, and one hot afternoon Suzie and I waded across the river to look at the San Bushman cave art we’d been told was hidden beneath the overhang.

We climbed from the river, stepped over a dead tree, and were soon under a great overhang of sandstone streaked black where rainwater had leached out minerals. The sand underfoot was soft and fine, covered with dassie spoor and the sinuous mark of a snake. And there, beyond a bone-white strangler fig, was a vertical rock wall covered in red ochre paintings of great beauty. Impala, jackal and zebra, holy eland and hunters who flew godlike on unfettered feet, spears poised. Suzie and I stared in awed silence. And later, at sundowner time, we wondered when it was that we had lost that hallowed feeling of blood-brotherhood with nature.

There’s so much other evidence of distant and ancient creation in the Waterberg’s mountains and gorges. Remnants of the very oldest known lifeform are present in the Waterberg. They’re known as stromatolites, a fancy word for the fossilized remains of ancient bacteria – microscopic, single-celled organisms thought to have emerged 3.5 billion years ago, just a billion years after the earth itself was formed.

The record of a clear chain of being is unbroken. There’s Sentinel Ranch, where researchers have found masses of dinosaur fossils dating back 250 million years to the Triassic and Early Jurassic. A real-life Jurassic Park, in fact, captured in stone. Most awe-inspiring is erythrosuchus – which means ‘red crocodile’ in Greek. A gigantic meat-eating monster, named not as some have claimed, for its red teeth but because its brutal conical fangs, serrated like sawblades, stained the rocks around the fossils a vivid blood red. This nightmarish creature apparently ripped its prey to bits in seconds. That’s easy to believe.

Closer to us in time are the hominin fossils at Makapans Valley, about forty clicks away, where our possible ancestors, Australopithecus africanus, lived and left their bones nearly 3 million years ago. This very early record, along with later settlements of our species in the area, suggest that the Waterberg has been home to a long uninterrupted lineage of living beings. Closer still to us, in about 1700, Iron Age Nguni settlers created hilltop settlements at Malora near the Palala River. Their well-crafted dry-stone forts survive to this day.

Elephant, rhino, lion and buffalo still inhabit the Waterberg, many reintroduced by Clive Walker and his dedicated team at the Endangered Wildlife Trust. Most intriguing, perhaps, is the chacma baboon. Which brings us to Eugene Marais, another of the Waterberg’s untamed and most beguiling inhabitants. Marais is important to this story not only because he lived in this enchanted place, but because his sensitivity and sharp intellect inspired him to study baboon behaviour and derive from his study a radical conclusion about the human psyche.

Marais is deservedly celebrated as a great Afrikaans poet. But he is also famous for his other writings on termites and the chacma baboon – ‘The Soul of the White Ant’, ‘My friends the Baboons’ and his major work, ‘The Soul of the Ape.’ But many people have no idea that Eugene Marais lived a brilliant, complex, multifaceted and tragic life. In his perceptive introduction to the 1969 first edition of ‘The Soul of the Ape,’ author of ‘African Genesis,’ Robert Ardrey, calls Eugene Marais ‘a human community in one man. A poet, an advocate, a journalist, a story-teller, a psychologist, and a natural scientist.’

Sadly, Marais was also addicted to morphine. As a youth he suffered cruelly from neuralgia; and morphine, at that time thought innocuous, was available without restriction. It was the only painkiller that brought relief. And, like the lurking crocodile in Marais’s own dark poem ‘Mabalel,’ the drug crept up on him silently, grabbed him, and destroyed his life. Perhaps it’s not surprising that he, a tormented genius like Vincent van Gogh, also died by his own hand.

Luckily for us and for science, in 1907, and long before he shot himself, Marais retreated to the Waterberg and its healing silences. The reasons for his move are complex. He was a broken-hearted widower; he wanted to get away from the city; he was using too much morphine; and he fancied himself as a mineral prospector. There was also the corrosive disillusionment he felt about the humiliation and devastation that his own people, the Afrikaners, had suffered during the Boer War at the hands of the British – scorched earth and concentration camps. Marais had studied in London to become a barrister, and this was not the behaviour of the English people he knew. The betrayal was deeply depressing.

After his arrival by ox-wagon in the Waterberg, Marais took up residence in a simple stone house, and soon became fascinated by an unusually large troop of baboons that lived in a nearby rocky krantz. When he first wandered amongst them, sitting on a nearby rock quietly to watch and take notes, the baboons were suspicious and aggressive. But tact and patience won and the troop finally accepted him.

Then, for three years, from dawn to dusk, Marais studied these complicated creatures; recorded their behaviour, and watched their social interactions. He was, in fact, the first man in the history of science to conduct a prolonged study of one of our primate relatives in a state of nature. As Robert Ardrey wrote in his introduction to ‘The Soul of the Ape, ‘…as a scientist he was supreme in his time, a worker in a science then unborn.’ That science is now known as ethology.

Marais the proto-scientist bewailed his lack of resources in the wilderness. He had no library, no scientific references. But this meant he also evaded what philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer has cited as the greatest flaw of systematised scholarship: ‘Education perverts the mind by obtaining ideas first and observations last.’ (Marais may well have read Schopenhauer, because he remarks, ‘We approached this investigation without any preconceived ideas, and although at the beginning inexperience may have left much to be desired in our methods, we at least had no theories to verify.’)

Marais looked at baboon behaviour with eyes untamed by any previous ideological bias. And what he concluded was indeed revolutionary. He used his insights to illuminate the evolutionary origins of the subconscious in humankind, writing: ‘I have an entirely new explanation of the so-called subconscious mind and its survival in man…’

He called this ageless distillate our ‘phyletic memory.’ (Science now recognises it as ‘phylogenetic’ memory.) At this point in my researches I had a sudden ‘Aha!’ moment. Marais’s phyletic memory corresponds so well with psychologist Carl Jung’s idea of the ‘collective unconscious.’

Jung saw the collective unconscious as a part of the human psyche inherited from our ancient forbears, containing impulses not learned during our lifetimes, but present in all humans from birth – an innate storehouse of intuitions, impulses and ancient memories, both malign and benign, that dates back to ancestors who first abandoned the relative comfort of the tropical forest and ventured out to make their living on the hot dry savannah.

That vast East African grassland glittered with menace and danger. Sabre-toothed cats, predatory eagles, hyenas and snakes killed our forebears by the thousand. To survive and flourish we needed a quick brain and a daring spirit. In truth, we might also have needed a cold heart. And it seems possible that we inherited that ruthlessness from our even more distant reptilian past. This museum lurks still in our brainstem, and is known to researchers as the ‘R-Complex.’

This is unsurprising. As we now know, the human mind evolved just like our bodies did – modifying inherited structures to suit our survival needs. We owe the structure of our arms, for example, to a transitional lobe-finned fish, known as Tiktaalik, that lived 375 million years ago. One bone, two bones, lots of hand bones, five digits. Part of our mind is at least that old.

Which brings me full circle to that feeling of déjà vu, that deep familiarity we all sense when we recognise a pretty fold of pale grassland in the bush, or see a red-earthed game path winding through trees and out of sight – even though we have never been to that place ever before in our lives.

True, we do not know the place personally; but our collective unconscious recognises it – because millions of years ago our ancestors saw similar places day after day, year after year, for millennia, while they lived and perished on the African savannah. Seeing and knowing those places conferred on them a survival benefit that endures. They bequeathed us these genetic memories. Their knowledge is coded into our DNA.

In the Waterberg, because evidence of an unbroken chain of being dates back to the stromatolites, the one-celled creature that was the earliest form of life on earth, I was compelled to recognise a one-ness that binds all species together. All of us are linked genetically to all other life forms found on earth. The evidence is overwhelming. We share about 96% of our genes with chimps, 30% with banana trees, and even share Histone H6 with peas and cows. The conclusion is inescapable. We are a part of nature, like ferns and worms and the sun, intimately bound together in a complex dance of molecules.

That brings me again to the shimmering sky I saw that night in the Waterberg. And we must thank a brilliant physicist, Margaret Burbidge for what comes next.

Margaret Burbidge proved back in 1957 that the chemical elements essential for all life are created deep inside stars by a process of nuclear fusion. Stars are, in fact, giant nuclear ovens, compressing together hydrogen atoms and brewing up the heavy elements needed for life. When, as supernovae, they explode, those elements are spewed out into the great emptiness of space – and this stellar residue contains the building blocks that make up our bodies and those of all living things: carbon, oxygen, iron, nitrogen, phosphorus and the rest. This means our kinship with other life forms dates back even earlier than the stromatolites, back to the earliest formation of the cosmos. We are made of stardust.

This deep connection between humanity and the universe is what gave me the conviction I mentioned earlier, that I belong here. This planet is our true home. That realisation is also the origin of the sense of wonder I feel each time I see a full moon rise, each time I watch an eagle ride the thermals, each time I stop and touch a baobab. I am part of nature; the trees are part of me, as are baboons, rats and kudu. My blood is their blood. We belong.

Albert Einstein understood. In a 1942 letter to a friend he wrote: ‘People like you and I, though mortal of course, like everyone else, do not grow old no matter how long we live. What I mean is we never cease to stand like curious children before the great mystery into which we were born…’

I feel the same. Wonder is sacred. It makes us cherish the earth, the cosmos, and all its mysteries. It is also a form of secular prayer. I belong in this universe, my lineage is true. This planet is our home.

David Lambkin is a PenguinRandomHouse author. His latest novel, ‘Whisper of Death,’ was published in June last year to critical acclaim. Visit davidlambkin.com

Anyone who has explored the wilder parts of Africa will recognise one of life’s more startling travel experiences.

You round a corner of a red dirt road somewhere out there in the middle of nowhere and suddenly it appears – a tiny trading store crouched in the bush just off the verge. Dust, relentless sun, acacias, baobabs, a tinker barbet tapping ceaselessly in the heat – and one lonely trading store.

The shop’s Coca Cola sign squeaks on rusted hinges in the hot wind, proudly announcing the owner’s name – Patel or Banderker or Singh. Never Smith or Trelawny. No. The proprietor of a typical African trading store – a ‘duka’ in Swahili – is traditionally a Hindu or a Muslim settler – he and his wife run the place. Both polite, both lonely in the wilderness, always with a guarded smile for the hot and weary traveller. And if you’re in luck, there’ll be a cold Coke to cut the dust before you continue your long trek to your distant destination across miles and miles of bloody Africa.

No matter where you encounter these trading stores – Zambia, Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Malawi, Botswana, Tanzania, Kenya or South Africa – they all smell the same. An aromatic blend of turmeric, chilli and joss, even a touch of paraffin or diesel; and, wafting from the adjacent kitchen, the mouthwatering scent of a spicy chicken or vegetable curry simmering on the hob.

You can find anything in these dukas, from a bicycle to a pair of wellies. You’ll spot those beige enamel teapots, for example, the ones with the green trim, and cheap Okapi folding knives so treasured by skinners, small rose-coloured bananas from Lake Victoria, three-legged pots, 4X4 tyres, soft baling wire, crowbars and viciously coloured pink sweets.

And these ubiquitous trading stores apparently predate even the earliest Western explorers. One of the Naipauls, VS or Shiva (I read this once but can no longer find it) states that the 19th century Western explorers like Burton, Speke, Baker and Livingstone would often come across a lonely duka hidden away in the unforgiving bush, long-established and miles from the nearest civilisation; the husband-and-wife owners astonished by the first white faces they had ever seen. And imagine the dismay of the Victorian explorers – always armed to the teeth and convinced they had penetrated to the heart of untamed Africa – only to find a pair of humble shopkeepers already doing business in the wilderness!

These trading stores are so much a part of my happy childhood and grownup memories, so filled with traveller’s delight, that encountering them today always brings a moment of poignant recognition.

Which is exactly what happened the first time I visited a remote bushveld farm in a valley at the foot of the Magaliesberg where I hoped to build my tented camp.

I turned off the tar onto the kind of red gravel road you encounter everywhere in Africa and pointed the nose of my 4X4 to the north. And then, after a few dusty kilometres, the little building suddenly appeared. A typical African trading store, right alongside the road, shaded by a palm tree – low, unpretentious, welcoming – its Coca Cola sign, battered by sun and rain, proudly announcing ‘Amod & Son.’

I slowed the car and turned to watch this fascinating apparition as I drove past. I decided instantly to return, meet Mr Amod and his son, and find more of the stories I want for my Storycatcher project. I knew that lovely tales of adventure and courage were hidden inside the little duka’s weathered walls.

When I returned to Amod and Son some months later after building my camp – nothing’s easy in Africa – I found not Mr Amod but his grandson, Mr Aziz Varachia.

Mr Varachia is a charming man who wears his years with great elegance. Politely remote, he has been tempered by Africa’s stern trials and is gently resigned to life’s imperfections. Africa, like the sea and Islam, teaches wisdom and submission.

The interior of Amod & Son is plain and echoey. Again, the similarity to other stores I’ve seen in other parts of Africa is quite remarkable. The place is dimly lit, has white walls and tall shelves that hold tinned veg, tinned curry, bags of rice and mealie-meal, bicycle tyres and inner tubes. A rackety compressor cools the Coca Cola fridge. There are full gas bottles, and glassed display cabinets containing everything from padlocks to combs.

But I wanted my stories. And I got them. While Sam Malesha, his assistant of ten years, bustled about serving customers, Mr Varachia and I began to chat across the counter about the present and the past. But first I had to get the genealogy clear in my mind…

Who was Amod? Who was the son? Where does the name Varachia come from?

Mr Varachia smiled. “My grandfather was Ahmed, which in South Africa somehow became Amod. My grandfather used to call my father Amod, even though his name was really Abdul Hay Varachia.”

So…everyone was and is a Varachia? Indeed.

Details of the Varachia family’s first arrival in South Africa are lost in the mists of memory but family legend has it that the Varachia grandparents took passage from Gujarat in India, sailing bravely to distant Durban in the mid-1800s.

A quick online look at the history of Natal gives us a tantalising insight.

In August 1843, Natal become a Crown Colony, ruled from distant Cape Town by a British Governor. The economy of the new colony was fragile. Bellicose Zulus were omnipresent (the humiliating defeat of British arms by Zulu impis at Isandlwana came in 1879) and the climate was maliciously tropical.

Yes, there was a harbour, Port Natal, and some far-sighted farmers already saw the potential for growing sugar-cane in the moist heat. There were, after all, tempting precedents. The Dutch had introduced sugar-cane to Mauritius back in 1639, and by 1748, the new French governor of Mauritius had opened the first sugar factory on the island. French profits soared; but willing farm labour was scarce in Durban. Warriors don’t do digging.

Then, in 1848, an entrepreneurial Natalian sugar farmer, a Mr E.R. Rathbone, imported labourers from India to work on his farms. This experiment was a huge financial success and, by 1859, legislation was passed in London that made it possible for the Natal Colony to introduce legal indentured labourers from India. On 16 November of that year the first group of 342 labourers duly arrived in Durban from Bombay on the sailing ship Truro.

It seems likely that early Varachia ancestors were amongst them; when I asked Mr Varachia what had brought his grandparents to South Africa, he replied simply, “They came as labourers.”

Interestingly, the surname Varachia has its origins in Gujarat, a seacoast province of India. The Gujarati word ‘Varach’ means a person who is skilled or expert. Whatever the history of the Varachia’s family’s arrival in South Africa, Mr Varachia’s first recollection of his family’s life as traders in Africa centred around the home built by his grandfather years before in the thick bush on the northern side of the Magaliesberg river. This house doubled as the first Varachia trading store.

“My grandfather had six sons, all of whom became traders of one sort or another. My grandfather lived and traded there out of that house, the first Indian gentleman to settle near Hekpoort.”

Around the late 19th century, the saga of the Varachia family takes us way up to Phalaborwa in the South African lowveld, by which time intrepid grandad Varachia was bartering trade goods with the Boer farmers in return for milk, butter, meat and eggs.

It must have been a tough life for the family. Up in the pre-dawn cold to pack trade goods into their ox-wagons – rope, steel, nails, timber, spices and tobacco, in-spanning sixteen to eighteen bullocks, and setting off for the unknown.

And think of how long it took! Ox wagons travelled ploddingly, covering at most sixteen kilometres per day; and Phalaborwa was over six hundred kilometres to the north, well away from the Varachia family home in the Magaliesberg valley. Forty days and nights! It’s almost biblical.

I ask about granny Varachia. Did she go on the trek northwards?

“No,” replied Mr Varachia. “She tended the original store and kept house.”

Brave woman, I thought. Given the snakes I encounter regularly in my own camp, she must have had a busy life in the bush!

It took guts too, to venture into the African wilderness on that northern journey. Phalaborwa lies in the humid tropical lowveld of South Africa and malaria is still endemic. Bilharzia, giardia and crocs infested the rivers, the big five roamed free, and in the mid-1800s the likelihood of bumping into a cocky young elephant bull or an unfriendly local with a spear was still high.

I asked if there was any written family record of those perilous trips.

“No,” said Mr Varachia, “nothing except stories, and the stories, unfortunately, just gradually disappeared.”

Mr Varachia’s father Abdul Hay inherited the Magaliesberg business when grandad Varachia – known as Amod – passed on, and built the present store, now run by Aziz, grandson of the original ‘Amod’. The young grandson learned the ins and outs of trading from his father and mother, who both worked in the store. The tiny pinkish house that stands alongside the present Amod & Son was originally a trading store too, open only at weekends.

It’s a story of a long tradition of family ownership, courage and grit. Mr Varachia’s father, I’m told, “Was working here in the store for maybe thirty years before I took over. And I have been running the place for ten, twelve years now, maybe fourteen.”

What, I ask, was it like to trade in the bushveld near remote Hekpoort in the old days?

In the old days, Mr Varachia says, farming was different in the Magaliesberg valley. “There was a lot of maize farmed, even wheat. In those days, he says, “We had feed in stock – you know, cattle feed, horse feed, like a proper farm shop, but that has now died down because our poor farmers here are struggling. It’s become very expensive for them to farm now, labour costs have soared. They don’t get enough money out their farming. So most of them have given up farming.”

I ask him about social interaction; and he tells me that in the old days the farmers often came to the store, had a coffee and talked about their farms, how business was going and the problems they faced.

The Afrikaans farmers were different in the old days, he remembers. They were more godly people then, more religious. They respected us, and we respected them, we had a good relationship with them, he said. We were all struggling, we struggled together, and we actually kept the poor farmers toiling on their farms. They were farming to feed their nation, so we opened books, you know, books of credit for them, in the understanding they should pay only when they had a good harvest.

And yet, I said, that was at the height of apartheid when you couldn’t go into the local cafe with them – but you could lend them money to keep them going. Seems unfair.

There was no such thing as apartheid between us, says Mr Varachia. They accepted us, and we accepted them.

And, because of their Islamic faith, which forbids usury, the Varachias didn’t charge the farmers interest. The Varachia family and other Muslims around Hekpoort were of enormous help to the local farmers. They gave credit and loans or even donated animal feed for nothing in the hard times.

And what about the future, I say. I see for sale signs here. Why is that? Have you not got a son to pass the business on to?

In fact, Mr Varachia has two sons, Abdullahi and Imran, but they’re not interested in living the life their parents lived. Nor do the Varachia’s daughters, Anisa and Aysha, want to face the trials that go with rural living in present-day South Africa. The children have moved on – to Johannesburg and America.

Mr Varachia smiles sadly. “Things have changed,” he says. “There’s a lot of crime out here every day now. Not a day passes but somebody’s bulls are stolen, somebody’s fence has been cut, somebody’s house is broken into. So it’s no more a place to be, you will be unsafe around here. You know, before – it was nice, it was safe, no crime. But nowadays, to live here is no more a pleasure.”

Mr Varachia has already started to scale down, buying less, stocking less. Which explains the many empty shelves I see around me.

His face is resigned as he says to me. “I can’t carry on. Somehow, you got to shut down. My wife Rashida feels the same. She told me, ‘I think we better sell up here.’ He nods. “It’s time to move on.”

And when you finally close up here, where will you and your wife go?

He ponders. “I don’t know where we’ll go, maybe to my daughters, maybe to Johannesburg.” He shrugs.

We shake hands – me, Mr Varachia and his assistant Sam – and I leave him and his echoing shop behind, climb into my 4X4 and reverse out. But before I drive back to my camp I stop and look once more at the little trading store. Images crowd my mind as I ponder the arc of the lives that will end here, soon, beside a red dirt road in the heat.

Ox wagons toiling through steep passes to the far north in the 19th century; the danger and the courage of the Gujarati traders; stoical grandma, minding the store in the middle of the inhospitable bush; the constant struggle for survival, the generosity of spirit that drove the Varachias to support desperate local farmers through drought and poverty; the dangers the first family members faced crossing the capricious Indian ocean on the three-masted barque Truro.

At the height of the shop’s success, Amod & Son was probably much like those I remember with such happiness from my childhood in Zambia and Zimbabwe; bustling, colourful, full of fascinating smells, noisy, part of the local community, a meeting place that stocked every necessity for rural living, everything from Zambuk to blue Dietz lanterns to Lifebuoy soap.

But I also realised that Amod & Son, standing there in fierce heat beneath its dusty palm, was more than a trading store. It was a monument to decades of courage and a testament to gentle kindness; the epitome of a whole family’s hopes.

Almost gone now. One day the relentless bush will reclaim the building, and people passing by will say, “Wasn’t there a trading store there in the old days?”

Then they’ll shrug and drive on.

Thanks to David Lambkin for adding his novelist’s touch to the story.

It’s late. Our convent dormitory in Harare is dark and hushed. Sister Avila and the prefects have stopped prowling the passages, stopped listening for naughty giggles and homesick weeping.

But four of us have shoved our beds closer together and are lying on our tummies munching Tennis biscuits. Our plan of escape is clear. We’ll save up and buy a London bus (red, of course) and kit it out with everything needed for a long trip to the north. Daringly, we decide there’ll even be room for boyfriends!

We’ll drive far away from school rules and routine, meet handsome Arab sheiks and ride camels across the desert. We’ll float in warm seas and collect shells the size of lampshades. We’ll smoke cigarettes and say “bugger”. And our best-selling diaries will be become setworks for Mrs Moffatt’s English class. Above all, we’ll never compromise. Our lives will be adventurous and scandalous – propelled by our bright red bus.

Well, it was not to be. Two of us got pregnant, one of us got married, and I got varsity. We all got trapped, I guess.

But a singleton’s shackles are easier to break because they’re not forged by vows made to others, and our adolescent promises to ourselves are quickly forgotten. So I smoked cigarettes and said “bugger” without my fellow conspirators. There were no affairs with Arabs. (My naïve image of romantic Arabs was defined by the movie Lawrence of Arabia. I thought everyone looked like Peter O’Toole – searing blue eyes gazing into the distance.) And sadly, there was no red London bus.

But, later, I did own a bush-green Discovery, named Disco Divine. And, despite Land Rover’s poor reputation, she didn’t break down in Zambia’s Bengweulu swamps, nor in Zimbabwe’s Mana Pools, but was considerate enough to go on sabbatical in Sandton. She seemed to enjoy this so much she took unauthorized sabbaticals time and again. So it was off to the chop-shop for Divine.

My next ticket to ride the backroads was Priscilla, Queen of the Desert. A sand-coloured Toyota Hilux that I pimped-up and kitted-out to the max. She had everything a suburban girl (with dogs, always with dogs) might need in the bush – but doesn’t really. There were even two large deep freezes. Mind you, those came in handy when I was in the Kalahari doing heritage preservation work with the Khomani San. Their desire for meat was prodigious – but was not matched by their desire to hunt. Why hunt when Patricia and Priscilla would provide? Never underestimate efficient refrigeration as a driver of cultural evolution!

Play-time in Priscilla came to an end when she was stolen while parked in one of Joburg’s burbs with everything on board: cameras, recorders, tents, tables, tanks, stores, the lot. Even the bloody freezers.

I took that as a sign. Time to upgrade to something that wasn’t high on the wish-list of car thieves and hijackers. And I was tired of sleeping on the ground, tired of being vulnerable to everything from claws to a knife. I wanted a bed.

Enter Alexandra, Queen of Everything! My dream home-on-the-move – stylish but comfortable, safe but unconfined, and capable of taking on terrible terrain without handling like a Sherman tank.

I’ve written about her in the “Meet my Truck” section on my website – but I haven’t shared the disappointment I felt once I’d done 20 000ks in her.

Why was I not hungry for more? I was living the dream. So why did I have that ‘so what’ feeling about it all? “So, I’ve seen the Augrabies Falls”, I thought. “So what”?

It took me a while to understand what I was not getting from my touring experience (although I can have fun with my dogs in a supermarket carpark!) Yes, I was going to places, but I was not meeting the people of those places. I wasn’t being touched by their hearts, I wasn’t hearing their precious memories of our country and its extraordinary inhabitants.

That is how Storycatcher came about – a project that would enhance both your and my sense of humanity and belonging. And, I figure, if I’m getting personal introductions, if I’m handed from storyteller to storyteller, told which roads to take and which to avoid, told where to camp and who to trust, I would never need to feel unsafe or purposeless again. The local people and I would share the important things, the things that really matter, laugh together and howl and learn from our shared stories.

And I want to share what I hear and experience. I don’t see the point of it all otherwise. Which is why I offer you my podcasts, videos and blogs. Treasures brought back from my travels.

Oh, and one last thing: I don’t smoke any more, but I do still say ‘bugger’!